Venture-funded startups are the innovation machine du jour. Uber, Airbnb, Google, etc. Whenever someone wants to make a change in the world, they start a company. Popular opinion is that startups can change anything but there are actually many constraints on startups. These constraints either kill the startup, prevent it from achieving its true potential, or prevent it from ever getting off the ground. The list of startups that failed to achieve their vision for one of these reasons is long. Transatomic Power was a company working on cheap and safe fission energy that just couldn’t get to market fast enough. Arguably, VC funding has forced a massive scope, level of hype, and timeline on several companies that led to a disappointing product. Many beloved services have been acquired and shut down by large tech companies. Outside of tech many drugs have been acquired and subsequently shut down because their funders needed to see an ROI. Would they have been successful by following another path? Maybe not. Maybe that path doesn’t yet exist.

There are several entities that can provide equity financing: the founders themselves, friends and family, crowds, wealthy individuals, private equity firms, and venture capitalists. I’m going to focus on VC funded companies because they dominate the current zeitgeist.

Constraints on VC Funded Startups

Need to Make a Lot of Money or Have Many Many Users

At the end of the day, a company needs to make money. VC funded companies need to have a chance of making a lot of money. I’ve seen people contort themselves justifying why their idea will eventually be able to make money more times than I can count. VCs sometimes claim they are willing to fund amazing things without consideration for how they’ll make a profit. That is largely just talk. Ultimately, all investors give money to VCs because they want a return on their investment (ROI). That ROI needs to be better than what they would get parking the money in a mutual fund. Not only do VCs need better ROI than other investment vehicles, but they compete with other VC firms for investor money. Inter-firm competition means that even if a startup can grow at 10%/month (which is still on target to crush the market at 3x annual growth), it will be unattractive if the “average” startup is growing at 15% a month. The need for ROI also means that the longer it takes for a company to generate a return, the larger the return must be because ROI is calculated not in absolute numbers, but as a % growth of money per year. At the end of the day ROI requirements mean that the idea needs to be a business that can sustain exponential growth or be valuable enough to a single existing company that they will acquire the startup and incorporate the idea into their own business.

At the end of the day, a company needs to make money. VC funded companies need to have a chance of making a lot of money. I’ve seen people contort themselves justifying why their idea will eventually be able to make money more times than I can count. VCs sometimes claim they are willing to fund amazing things without consideration for how they’ll make a profit. That is largely just talk. Ultimately, all investors give money to VCs because they want a return on their investment (ROI). That ROI needs to be better than what they would get parking the money in a mutual fund. Not only do VCs need better ROI than other investment vehicles, but they compete with other VC firms for investor money. Inter-firm competition means that even if a startup can grow at 10%/month (which is still on target to crush the market at 3x annual growth), it will be unattractive if the “average” startup is growing at 15% a month. The need for ROI also means that the longer it takes for a company to generate a return, the larger the return must be because ROI is calculated not in absolute numbers, but as a % growth of money per year. At the end of the day ROI requirements mean that the idea needs to be a business that can sustain exponential growth or be valuable enough to a single existing company that they will acquire the startup and incorporate the idea into their own business.

Venture capital portfolios are also designed around the expectation that while most of the companies will be worth nothing, a few will have incredibly large exits and ‘make the fund.’ This strategy allows VCs to take risks that other investors will not but means that any startup that wants VC money needs a chance at becoming worth hundreds of millions or more. There are many valuable innovations that just won’t be worth hundreds of millions of dollars on their own.

Need to Conform to Investor Timescales

VC firms technically return funds on timescales of ten or more years. However, they raise a new fund approximately every three years. The most important reason LPs invest in a new fund is the performance of previous funds. That performance pressure forces VCs to seek intermediate results in the form of higher valuations from their companies within one to three years that they can show to LPs when they raise a new fund. Therefore, VC fundable companies are constrained to ideas that can increase in paper value within a year or two. Now, the factors in a startup valuation can vary depending on several factors: how much pressure the investors are under, their understanding of the project, how much they care about the project, and the charisma or reputation of the founder. The charisma factor is arguably what enabled many of the most ambitious startups we’ve seen in recent years: Uber, Rigetti, SpaceX, and more. (See the “Need a Great Story” constraint for more.)

VC firms technically return funds on timescales of ten or more years. However, they raise a new fund approximately every three years. The most important reason LPs invest in a new fund is the performance of previous funds. That performance pressure forces VCs to seek intermediate results in the form of higher valuations from their companies within one to three years that they can show to LPs when they raise a new fund. Therefore, VC fundable companies are constrained to ideas that can increase in paper value within a year or two. Now, the factors in a startup valuation can vary depending on several factors: how much pressure the investors are under, their understanding of the project, how much they care about the project, and the charisma or reputation of the founder. The charisma factor is arguably what enabled many of the most ambitious startups we’ve seen in recent years: Uber, Rigetti, SpaceX, and more. (See the “Need a Great Story” constraint for more.)

Need an Exit Strategy

At the end of the day, venture capitalists need to return money to their own investors. This means that any startup they invest in must have an ‘exit’ strategy, or liquidation event where all the money tied up in the startup’s equity can become liquid cash. At the time of this writing (late 2018) that means either an initial public offering, where the equity becomes tradable on a public stock exchange, or an acquisition, where another company acquires all the equity in exchange for cash. The exit strategy constraint means that the startup needs to become valuable to a single acquirer or start generating enough cash to be valuable on the public market. Therefore, anything that has distributed value to many entities but little concentrated value is out.

At the end of the day, venture capitalists need to return money to their own investors. This means that any startup they invest in must have an ‘exit’ strategy, or liquidation event where all the money tied up in the startup’s equity can become liquid cash. At the time of this writing (late 2018) that means either an initial public offering, where the equity becomes tradable on a public stock exchange, or an acquisition, where another company acquires all the equity in exchange for cash. The exit strategy constraint means that the startup needs to become valuable to a single acquirer or start generating enough cash to be valuable on the public market. Therefore, anything that has distributed value to many entities but little concentrated value is out.

Need a Great Story

A key characteristic of a startup is that it is expected to change and grow significantly over time. “Past returns are not suggestive of future profit” to the extreme. Therefore any decision about the startup can be only vaguely data-driven at best; the majority of investor faith is based on a story. Stories are told by people, primarily the founder. There are many ways to weave a convincing story - personal history, amazing writing or speaking abilities, amazing demos, or to pulling together early data into a compelling tale. At the end of the day, the survival of the startup depends on its leaders’ ability to plant and grow belief in a story. The leaders need to convince not only investors, but employees, external allies, and customers as well. If the story isn’t there, no matter how good the idea is or how solid the plans are, the startup will die.

A key characteristic of a startup is that it is expected to change and grow significantly over time. “Past returns are not suggestive of future profit” to the extreme. Therefore any decision about the startup can be only vaguely data-driven at best; the majority of investor faith is based on a story. Stories are told by people, primarily the founder. There are many ways to weave a convincing story - personal history, amazing writing or speaking abilities, amazing demos, or to pulling together early data into a compelling tale. At the end of the day, the survival of the startup depends on its leaders’ ability to plant and grow belief in a story. The leaders need to convince not only investors, but employees, external allies, and customers as well. If the story isn’t there, no matter how good the idea is or how solid the plans are, the startup will die.

Need to produce a scalable product.

Products are a complete package that makes an invention useful to a consumer or market. Under many circumstances this constraint actually helps an idea become an impactful innovation: you can’t just build a better mousetrap, you need to grab the world by the collar and drag it kicking and screaming to your door. However, this constraint also means projects can fail to make an impact because either the market doesn’t exist yet (but might in the future) or because the team is amazing at creating the core insight but bad at productization, which often requires a different skillset. All businesses need to produce a product but VC fundable startups have the additional constraint that their product needs to be scalable - having a very low marginal cost for each additional customer - or have extremely high margins.

Need to Break Development into Correctly Sized Stages

A startup needs the ability to hit progress/derisking milestones with the amount of money typically raised in each venture round. VC funding happens in fairly standard round sizes: The first round is almost always <$3m. If you need $8m or $30m before your first major milestone, it’s hard to fund the project with VC money.

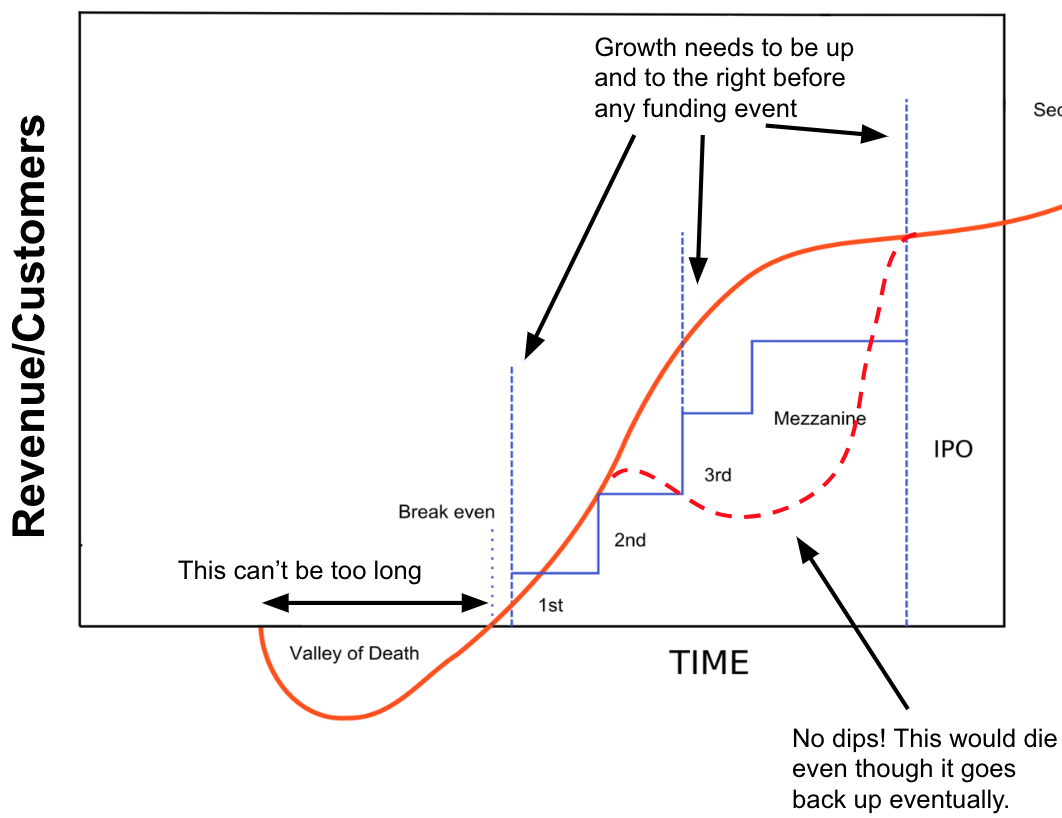

Need Specific Growth Curves

- The Valley of Death must be small. Most VCs will not fund a company that spends too long with low revenue or few users. This is another manifestation of the timescale constraint.

- Growth must be monotonic (always going up and to the right.) In rare circumstances a startup can survive flat or declining growth for a period if its management had the foresight or luck to raise funds before the lackluster growth that last until the growth resumes up-and-to-the-rightness.

Another way of visualizing these constraints

Another way of visualizing these constraints

If a potential innovation checks off all of these constraints, wonderful! However, many don’t. Maybe it should use a different channel to impact the world. Maybe the right channel doesn’t yet exist.

Thanks to Ti Zhao and Leo Polovets for reading drafts of this

If you enjoyed this post, please share!